Over the past decade, design thinking seems to have taken the world by storm. While more people are familiar with the basics, its popularity has also led to some confusion and even controversy.

Having engaged in this dialogue for several years, I am excited to share in this article all you need to know about design thinking so you can use it in an informed, conscientious way, should you choose to.

Click to jump ahead:

- What is design thinking?

- Who uses design thinking?

- What is the purpose of design thinking?

- Phases of design thinking

- Critiques and considerations

- Using design thinking for infographics

What is design thinking?

Design thinking is a hands-on, non-linear process for creative problem solving.

At its heart, the design thinking process is about emphasizing what’s important from the perspective of people impacted by the problem and the solution, in addition to considering what’s feasible and economically viable.

Design thinking is also a mindset, one that emphasizes empathy, curiosity, creativity, collaboration, action, and adaptation.

Design thinking emphasizes that while this mindset is inspired by the work of design, it is not exclusive to those who consider themselves to be professional designers.

“Design thinking is a way of finding human needs and creating new solutions using the tools and mindsets of design practitioners. When we use the term ‘design’ alone, most people ask what we think about their curtains or where we bought our glasses. But a ‘design thinking approach’ means more than just paying attention to aesthetics or developing physical products. Design thinking is a methodology. Using it, we can address a wide variety of personal, social, and business challenges in creative new ways.”

— David Kelley, IDEO founder, and Tom Kelley, Partner

Who uses design thinking?

Over the past decade or so, design thinking has become more well-known and has been applied well beyond the design field. People use design thinking to come up with innovative solutions to solve complex problems.

The design thinking process has been used to develop new healthcare products, improve government services, rethink transportation systems, and address complex global challenges such as food insecurity and equitable education.

What is the purpose of design thinking?

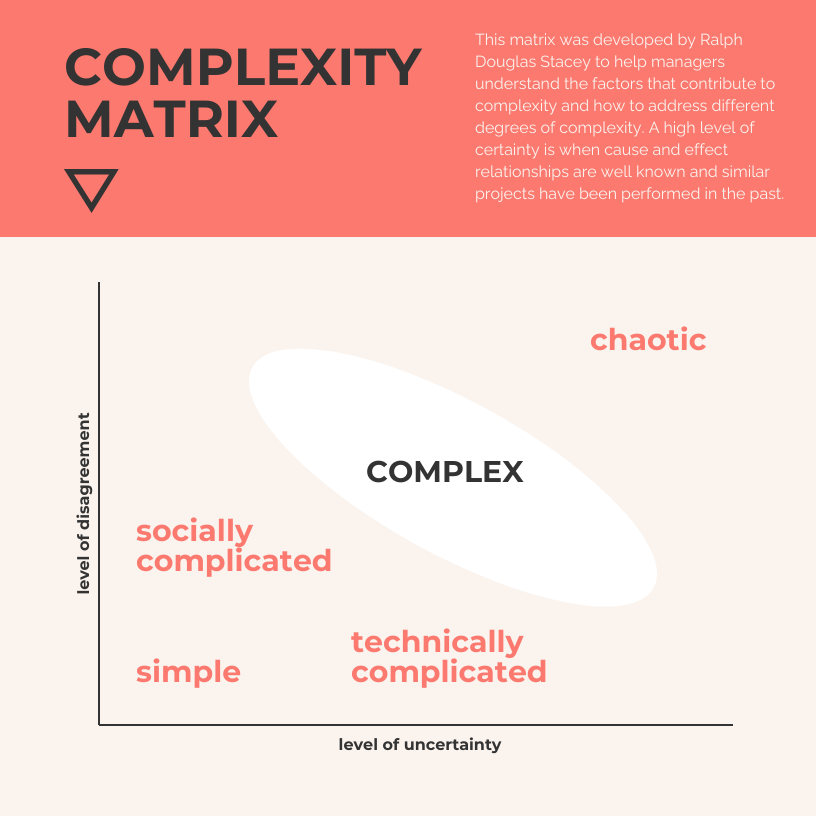

Design thinking is known for being most effective in situations where problems are not well understood. It’s also ideal for fostering big, transformational changes, rather than day-to-day incremental ones.

Teams and organizations use design thinking methodology to:

- Better understand the needs of customers, users, and people experiencing problems

- Learn and make improvements more quickly

- Reduce risks associated with launching new programs, services, and products

- Cultivate buy-in among stakeholders

Because design thinking is a process and a mindset, it unlocks numerous possibilities for creating new opportunities.

“The excitement over design thinking lies in the proposition that anyone can learn to do it. The democratic promise of design thinking is that once design thinking has been mastered anyone can go about redesigning the systems, infrastructures, and organizations that shape our lives.”

— Shelley Goldman, Stanford School of Education, and Zaza Kabayadondo, Design Thinking Initiative at Smith College

Phases of design thinking

It’s important to understand that design thinking is a non-linear process, which means the phases are not always sequential, can run in parallel, and are often repeated at various points in time.

That being said, those who are less familiar with design can learn about the process more easily by beginning to work through the phases in discrete, concrete ways.

“Experienced designers often complain that design thinking is too structured and linear. And for them, that’s certainly true. But managers on innovation teams generally are not designers and also aren’t used to doing face-to-face research with customers, getting deeply immersed in their perspectives, co-creating with stakeholders, and designing and executing experiments. Structure and linearity help managers try and adjust to these new behaviors… In most organizations the application of design thinking involves seven activities. Each generates a clear output that the next activity converts to another output until the organization arrives at an implementable innovation. But at a deeper level, something else is happening—something that executives generally are not aware of. Though ostensibly geared to understanding and molding the experiences of customers, each design-thinking activity also reshapes the experiences of the innovators themselves in profound ways.”

– Jeanne Liedtka, Harvard Business Review

Here is a summary of the phases, though they can go by slightly different names.

Empathize

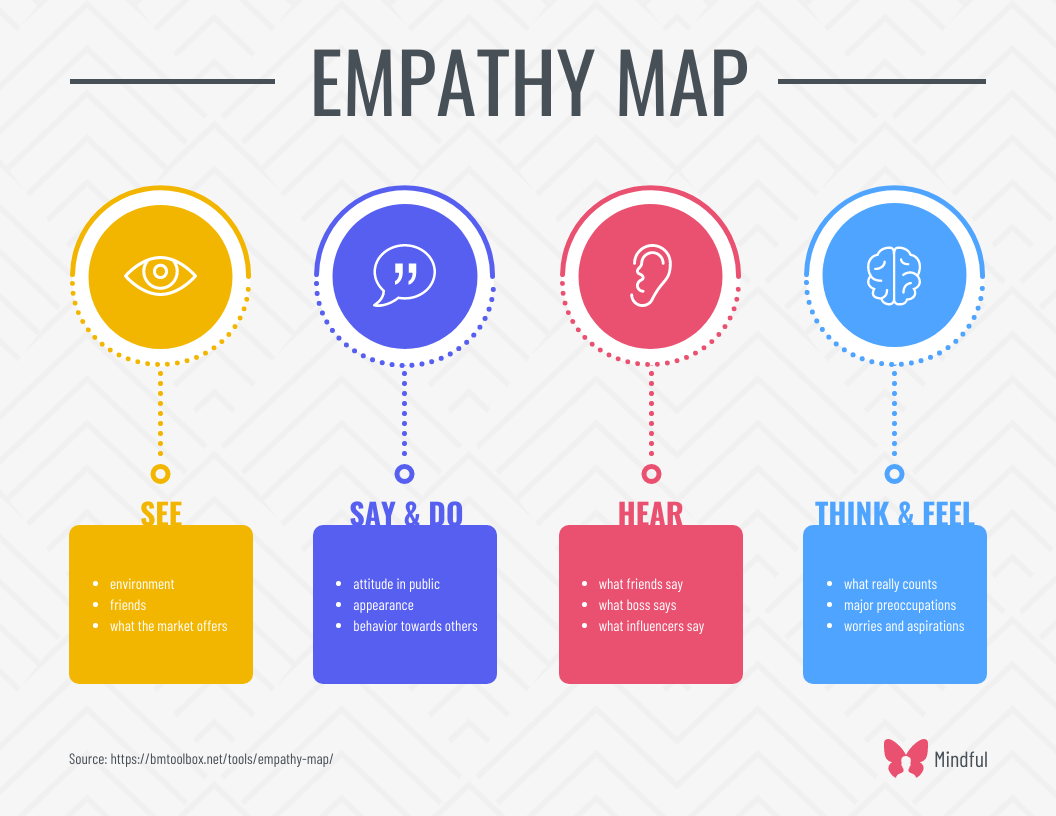

In this phase, research is conducted to gather more information about the people impacted by the problem, their needs and desires, their thoughts and behaviors, etc.

Rather than only looking at data, there’s an emphasis on experiencing what the customer experiences. This is why design thinking is often correlated with human-centered design.

Research activities can include focus groups, interviews, and real-life observations.

Define

The research is synthesized to pinpoint core problems and potential opportunities for creating potential solutions. This is generally done in a group and/or small teams, which not only helps everyone have the same information but also allows for multiple interpretations and therefore deeper insights.

Importantly, sometimes the problem identified is not the one the group thought they’d set out to tackle. It may be different, broader, or more nuanced than it was originally assumed to be.

Sometimes, these insights are summarized in documents such as empathy maps, personas and user journeys.

Ideate

Then comes the ideation phase. Once there’s a definition of specific problems and opportunities, a team starts brainstorming and generating ideas.

Team members are encouraged to come up with as many ideas as possible, as it fosters wild, outside-the-box thinking.

By focusing on possibilities instead of constraints, teams are able to challenge the status quo.

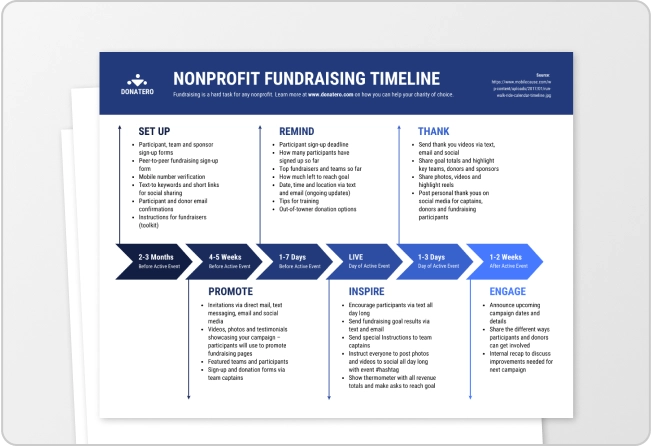

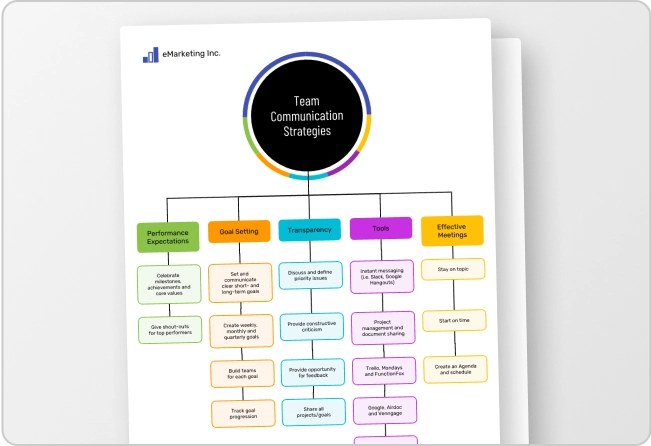

Oftentimes, ideas are captured in post-it notes, mind maps, or flowcharts.

Prototype

This is when ideas start to come to life. Instead of settling on and running with specific ideas, prototypes allow teams to experiment with potential solutions while making low investments in them.

Prototypes are rough, tangible representations that allow for early assessment of feasibility and other concerns. Creating multiple prototypes also allows teams to experiment with various ideas before preemptively committing to one.

Prototypes can be paper sketches, storyboards, mockups, or other proofs of concept.

Test & Iterate

Within the design thinking process, the testing phase takes place when the prototype is shared with real people (customers, users, etc.) to learn whether it truly solves the problem and how it might be improved.

The results of tests can be used to re-assess and redefine assumptions such as who the customer is, what the problems are, and which solutions might best fit their needs.

Learning in the testing phase can be documented in presentations, reports, or even infographics, which can help the team recall such learning in the future.

Testing is something that continues to occur so the prototype can be refined over time. Iteration not only improves the outputs and outcomes, but over time it also reduces the team’s normal fear of change.

Implement

Considered the final stage of the design thinking process, this is when design thinking becomes design producing.

The success of design thinking lies in the impacts it creates, and this phase is where the rubber hits the road. This is usually where the bulk of the time, money, and energy is spent.

The product, service, program, or whatever is being created is launched into the world, and the design team continues to research, reflect, and revise it as needed.

Design thinking: Critiques and considerations

While design thinking has received a lot of attention and applause over the past decade, it is certainly not above criticism. Here are a few questions to keep in mind when design thinking is being applied to creative problem solving.

Who are the humans being centered?

The linchpin of design thinking is the very first phase: empathize.

While empathy has become more of a buzzword, it remains a skill that is rare because of its difficulty.

Some of the difficulty lies in the fact that power decreases empathy, and power is generally something more sought after and rewarded. This is especially relevant because it’s often people in positions of power that are looking to use design thinking.

What too often happens is that teams are largely homogeneous, and the voices of people in positions of power are valued more. Sometimes it’s the professional designer that carries privilege, acting like gatekeepers who “police” or control the process and outcomes. Sometimes it’s the client or funder who is centered in the process, rather than the humans who are most impacted by the problem and/or solution. These decision-makers preserve the status quo, according to Harvard Business Review.

An example is the very common design thinking exercise known as “How might we?” This exercise invites the people in the room to consider how they might solve a problem. But the more empathic thing to do, according to Tricia Wang’s article for Fast Company, would be to ask “Who should we talk to?” or “Why are we doing this?”

The important thing to remember is that the ideas that are generated and selected are not guaranteed to be about the end-user, customer, or person impacted, which is tragically the whole point. While the promise of design thinking is that it disrupts the status quo and even challenges traditional biases, it takes more than a list of the phases to make that happen.

Co-design with many stakeholders usually takes very humble facilitation as well as a lot of time. Teams need to be diverse to truly innovate (Harvard Business Review has more on how) and people need to trust each other to feel comfortable enough to share daring, new ideas. This will likely require more than design thinking, but it’s the best shot teams have at reaching some of the aspirations of design thinking.

Is design thinking being thought of as a “silver bullet”?

Design thinking is not a panacea.

While it has been useful for many and varied situations, design thinking is not useful for every situation. It’s not the scientific method, it’s not statistical analysis, it’s not Six Sigma (process improvement), and it’s not ethnography, even if it draws some influence from each of these.

Design thinking is best used for problems that lie in a sweet spot between those with obvious solutions and those with a high level of uncertainty, such as climate change.

Let’s face it: these days, there’s a lot of uncertainty, so it’s wise to consider how design thinking might be useful as well as its limitations. Many problems cannot be solved simply with more products or services.

The major thing to understand is that, as designer and educator Lee-Sean Huang puts it, design thinking is a means, not an end.

If a team decides to use design thinking, they must commit themselves to an iterative process that supports the development and implementation of an effective solution. It takes ongoing practice and work, and the reward is in seeing outcomes for people change.

Is design thinking being used as a substitute for deeper thinking and engagement?

It’s tempting for companies looking to innovate quickly to sidestep the real work of design thinking. They want creativity without the mess, which is like wanting a lush vegetable garden without the necessary rain (and mud). Even Michael Hendrix, a partner at the design-thinking-proponent firm IDEO, has called this a mere “theater of innovation.”

Design thinking requires a certain kind of critical thinking, one that it takes years of devoted practice for professional designers to hone. This is why designers can be instrumental guides or facilitators, even if they can never substitute for inclusive, participatory teams.

Creativity of the design kind requires some ability to embrace complexity, and to humbly admit that we each perceive problems and solutions through individual lenses which are inherently personal, political, cultural, and professional.

“This is Design Thinking’s fatal flaw,” designer Jesse Weaver says. “It ignores the reality in which it is designed to operate.”

A well-known story in design thinking critiques is that of the PlayPump, a technology that was meant to bring drinking water to thousands of African communities but failed because of a very superficial understanding of the culture it was embedded in (and other factors described in The New Republic).

As mentioned before, it’s difficult to cultivate innovation without diversity, inclusion, trust, and a “creative atmosphere”, as stated by entrepreneur and community leader Mohamed Fakihi.

For teams to present bold ideas and to act on them, they need to feel they have the freedom to fail, that in the midst of ambiguity their team has their back, that it’s okay to get “messy.”

Without these essential components of creativity, design thinking is just another day at the office, and the results are sure to be status quo.

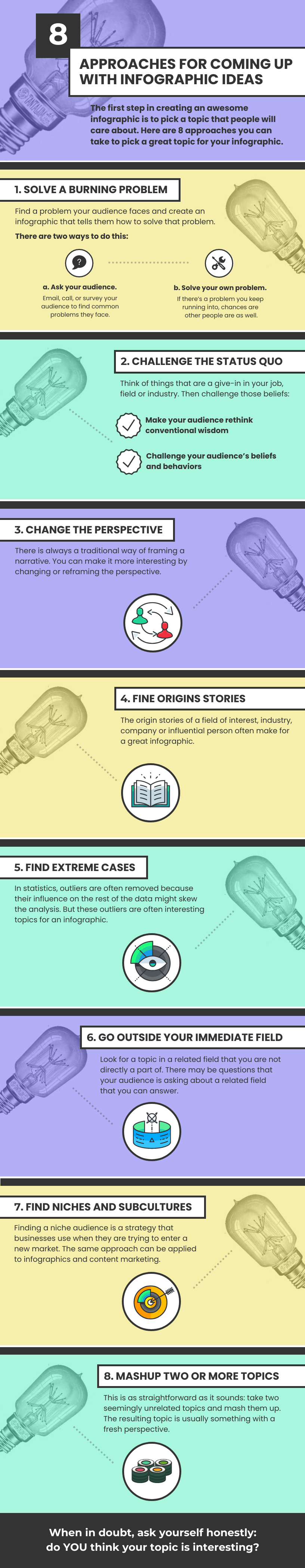

Using design thinking for infographics

As previously mentioned, the design thinking process is useful for many situations and creations, and that includes infographics. Here are a few ideas for how to use design thinking principles and practices to inform the creation of your infographics.

- Identify a burning question others are looking to answer, then create an infographic to answer it.

- Consider creating an infographic that is centered around stories of people’s experiences, opinions, and/or needs.

- Assess whether your infographic could and/or should include data, information, perspectives, or insights you hadn’t originally considered.

- Early in your process, push yourself to sketch as many different layouts for your infographic as you can, and see what fresh ideas emerge.

- Before you polish your infographic, share sketches or drafts with other people to learn how to make them even better.

- Ask yourself: Who exactly are the humans being centered by the stories in the infographic?

Summary: Design thinking aims at creative problem solving, which fosters technical and social innovation and more

Design thinking is inherently human-centered. Since humans are in some way a part of every problem and solution we’re interested in, we can use design thinking processes, practices, and principles to approach almost any situation, even if we aren’t “designers.”

What matters is that we’re critical and cautious about our approach, so we can maximize the usefulness of design thinking and minimize our natural inclination to stick with the status quo.

Design thinking is not merely a set of tools but a set of skills, ones that we need to work to develop over time. This is how we can make sure transformation truly happens.

Incorporate your design thinking process with actual designs you can customize using Venngage’s easy-to-use templates and drag-and-drop editor, as you can see from the templates above. It’s free to get started.