Travel Infographics Templates

Capture your travel experiences visually with Venngage's travel infographic templates. Share destinations, itineraries, and tips in engaging formats that transport your audience to new horizons.

Filter by

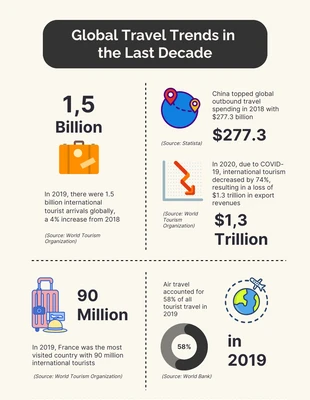

travel infographics

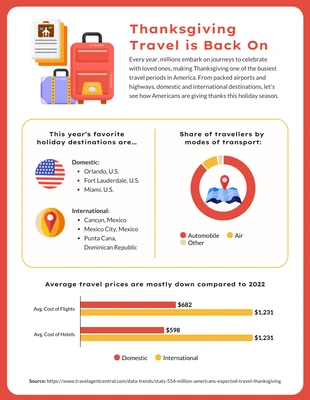

travel infographics

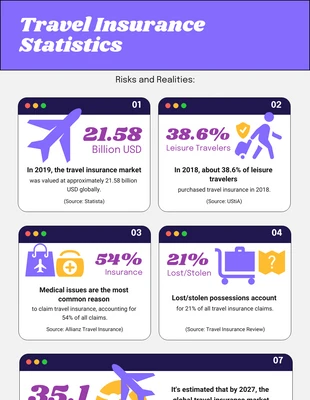

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

travel infographics

Popular template categories

- Brochures

- Mind maps

- Posters

- Presentations

- Flyers

- Diagrams

- Reports

- White papers

- Charts

- Resumes

- Roadmaps

- Letterheads

- Proposals

- Plans

- Newsletters

- Checklist

- Business cards

- Schedules

- Education

- Human resources

- Ebooks

- Banners

- Certificates

- Collages

- Invitations

- Cards

- Postcards

- Coupons

- Social media

- Logos

- Menus

- Letters

- Planners

- Table of contents

- Magazine covers

- Catalogs

- Forms

- Price lists

- Invoices

- Estimates

- Contracts

- Album covers

- Book covers

- Labels

- See All Templates